How the health crisis revealed the need for a new adaptability

At the end of the lockdown, the observation was clear: our accommodation lacks generosity, brightness, access to an outdoor space (garden, terrace, balcony, loggia, etc.), flexibility. Our office buildings have become obsolete in light of new ways of working. Our cities lack “space”, breathing, comfort, and amenities that would make density acceptable. In short, architecture and the city as we know it and think of it lack adaptability.

Living and working functions are more closely linked than ever, and the health crisis has only reinforced pre-existing trends such as working from home, and highlighted the limitations of the office building design model in the face of social distancing barriers and imperatives. Our dwellings are no longer designed solely for residential use, and the architecture of office buildings must incorporate more than just day-time work. We need to rethink our organisational models (living, working, moving, consuming, etc.) and imagine a reversible and adaptable architecture (temporary or permanent, depending on the context) in response to the evolution of our needs and uses.

The health crisis is compounded by a housing and environmental crisis

Given the shortage of housing in France and the environmental challenges of the construction sector, reversibility thus becomes a major asset of the circular economy both from the point of view of eco-construction and from the point of view of land recycling and the fight against the urban sprawl.

Faced with the increasingly rapid obsolescence of office buildings, growing numbers of developers and lessors are initiating this type of project. They are most visible in big cities because the profitability of housing is similar to that of offices and the complementary dynamics of office overproduction and chronic housing deficit are most pronounced there.

What are the issues with converting office buildings into dwellings?

As a prelude to research on the reversibility of offices/dwellings, attention must be paid to operations that have already taken place to transform offices into dwellings, in order to understand the difficulties and to identify points of vigilance.

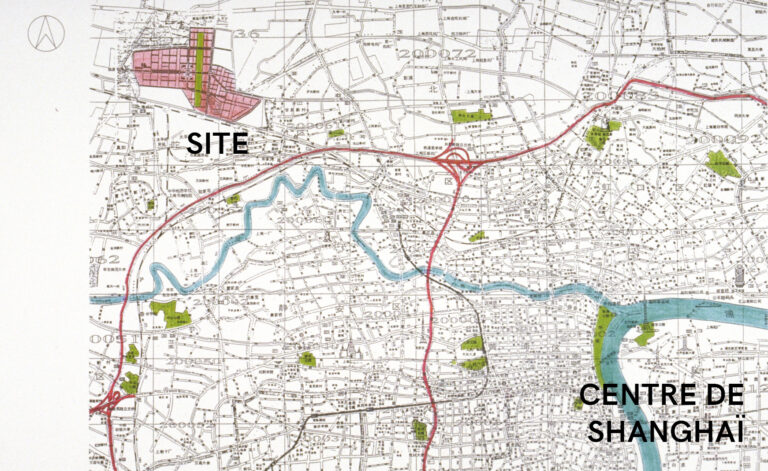

Based in particular on the analysis of the APUR on “La transformation de bureaux en logements à Paris de 2001 à 2012”, we can identify three main types of conversions: historical buildings prior to 1900 (notably Haussmannian buildings), buildings from the 1940s to the 1970s, and buildings from the 1980s and beyond.

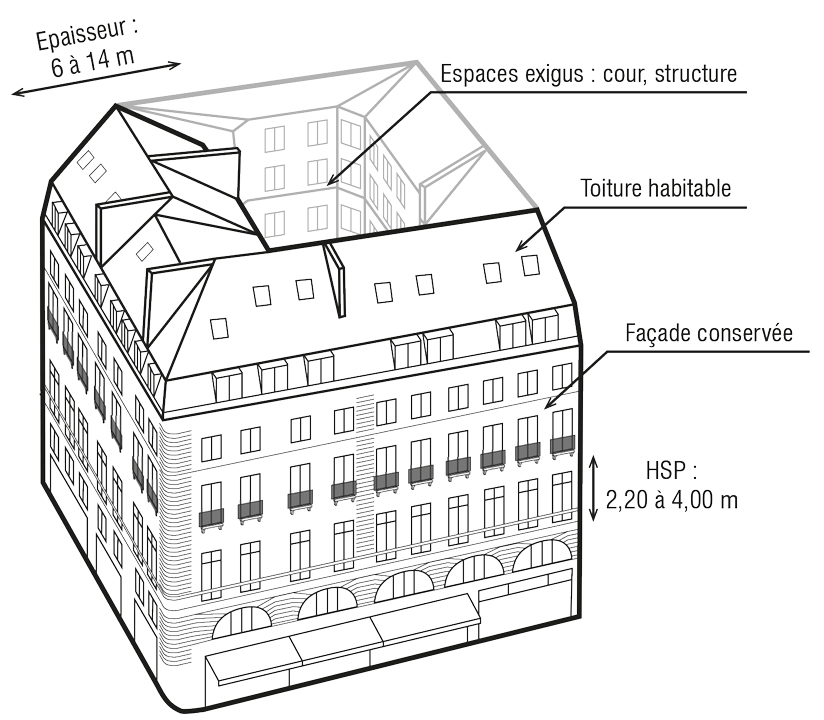

HISTORIC BUILDINGS:

These buildings have often already been converted from dwellings into offices before being reconverted back into housing. They therefore have propitious dimensional characteristics: thickness of 6 to 14m in dual orientation, ceiling heights of 2.20m to 4m, and facade openings already specific to housing plans. On the street, the stone facades impose an insulation from the inside, and in the courtyards, the less-worked facades in plaster allow for insulation from the outside. The renovation of roofs with skylights or dormer windows provides additional housing surfaces in the attic.

On the other hand, one of the difficulties lies in the structure of shear walls and in the small size of the courtyards, which sometimes make the layout difficult, particularly with regard to the addition of wet rooms – to meet PMR standards – which were not originally planned. Similarly, the creation of staircases for new vertical circulations according to standards is complicated (wooden floors, etc.) and expensive.

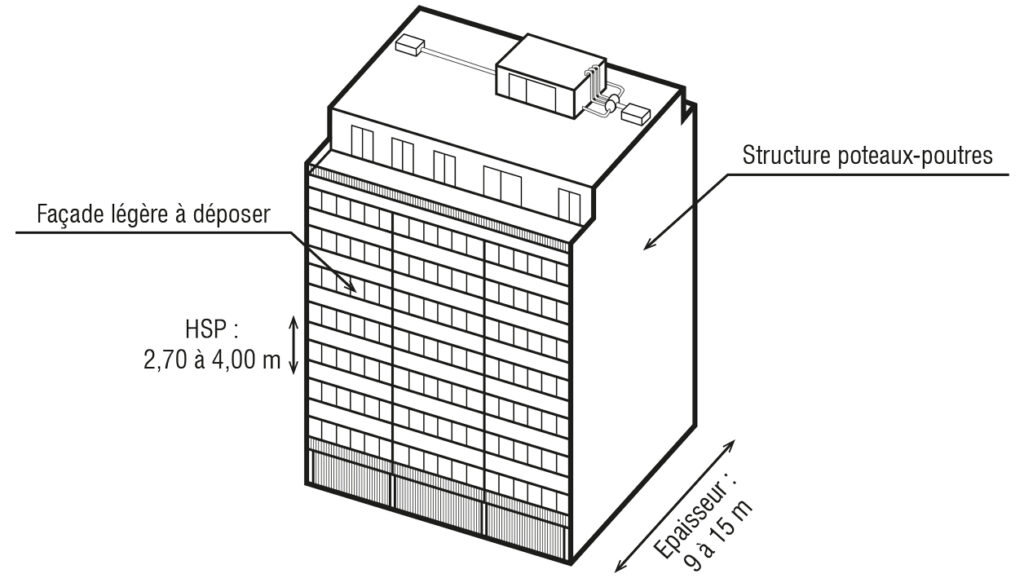

BUILDINGS FROM THE 1940s-1970s:

These buildings, intended for office use from the moment they were designed, nevertheless present interesting features for their transformation into housing. The architecture of these office buildings, based on a column-beam structure, their thickness from 9 to 15m and their ceiling height from 2.70 to 4.00m allows the design of the apartments to meet current requirements.

However, this flexibility in design is offset by a relatively high cost of work: total removal of light facades that are too extensively glazed and not well-insulated, major asbestos removal work, etc.

.

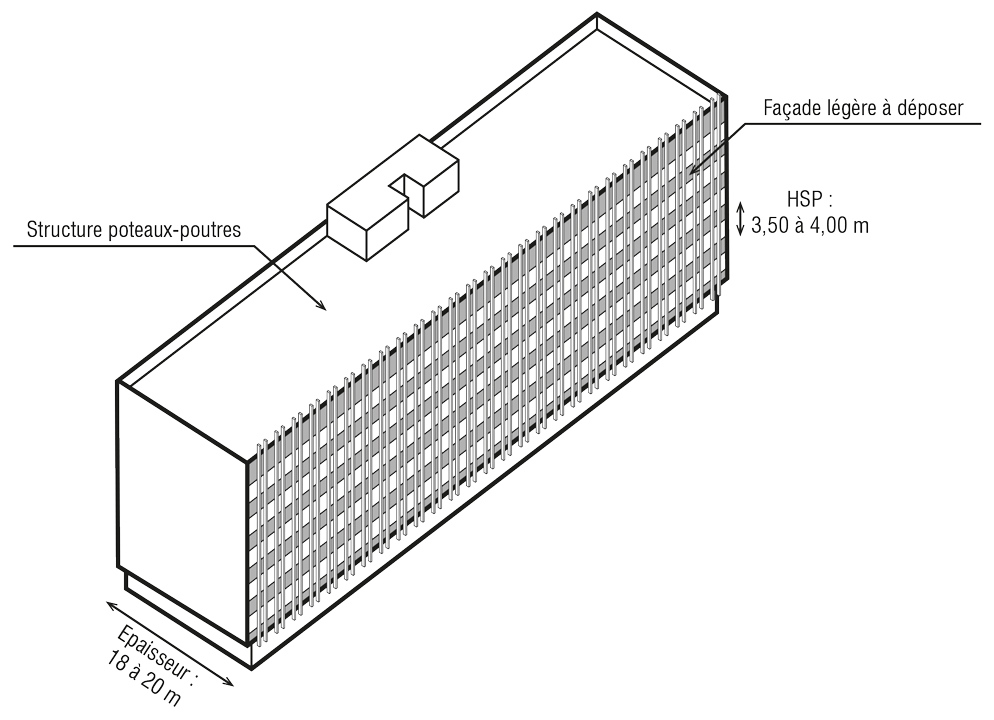

BUILDINGS FROM THE 1980s AND BEYOND:

Since the 1980s, the architecture of office buildings has had to meet objectives of maximum profitability, with increasingly specific characteristics: thickness in dual orientation up to 18 or 20m, ceiling heights of 3,50 to 4,00m with false ceilings and/or false floors, extensively glazed facades and sometimes very thin concrete floors.

These types of buildings are less easily converted. Despite the freedom offered by the column-beam structure, the excessive thicknesses of the buildings require the creation of patios or courtyards to provide the natural lighting necessary for the dwellings.

.

Reversibility of offices into housing: transformation of the Orion tower in Montreuil

In general, it can be noted that office buildings from the 1940s and 1970s are overrepresented in current office-to-housing projects. The freedom of arrangement allowed by the column-beam structure as well as their dimensional characteristics, close to those of residential buildings, make them the most interesting and recurrent studies in our recent practice.

.

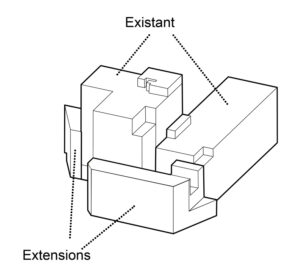

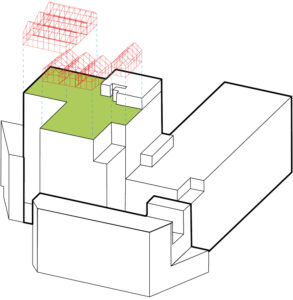

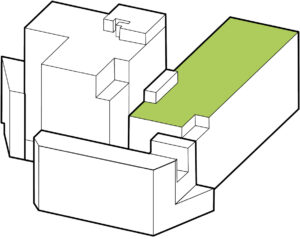

This was the case of the study we conducted in Montreuil for the transformation of the Orion office tower into a housing unit devoted to co-living. The study of this building allowed us, for example, to propose the adaptation of the frame of the apartments to the classic office frame of 1.35 m. The layout of the housing units was therefore adapted to the façade of the existing building. A new façade was proposed for the extensions.

.

It remains to be noted, however, that even if certain conditions for conversion are fulfilled by the existing buildings, the questions of fluid management, fire regulation, insulation and ventilation systems in particular still require significant studies in the context of a reversible building from the moment that it is designed.

-

Vivian Cloez Architect, Associate

TRAINING

Architect D.P.L.G – Ecole supérieure d’architecture de Paris-La Villette (2006)

DEA – Architectural and Urban Project – Theories and Devices – Ecoles d’architecture de Paris-Belleville, La Villette, Malaquais et Université Paris 8 (2005)

DPEA – Architecture of territories and urban projects – Ecoles d’architecture de Paris-Belleville, La Villette et Malaquais (2005)

Diploma of architect and urban planner – Federal University of Minas Gerais – UFMG, Belo Horizonte / Brazil (1999)