Alternative Rainwater Management, another way of bringing nature into the city

Architecture and Rainwater Management

Alternative rainwater management, another way of bringing nature into the city

As architects, urban planners and landscapers, we work together on land management within a pluridisciplinary agency, alongside promoters, developers and local authorities.

Landscaping, located at the heart of reflections on urban density, involves taking into account the scarcity and fragility of natural elements, in order to make nature exist sustainably in the city, and in the very heart of buildings. This enables us to put forward an overall management approach for water, from the buildings’ rooves to the ground of the plots, and into the public space.

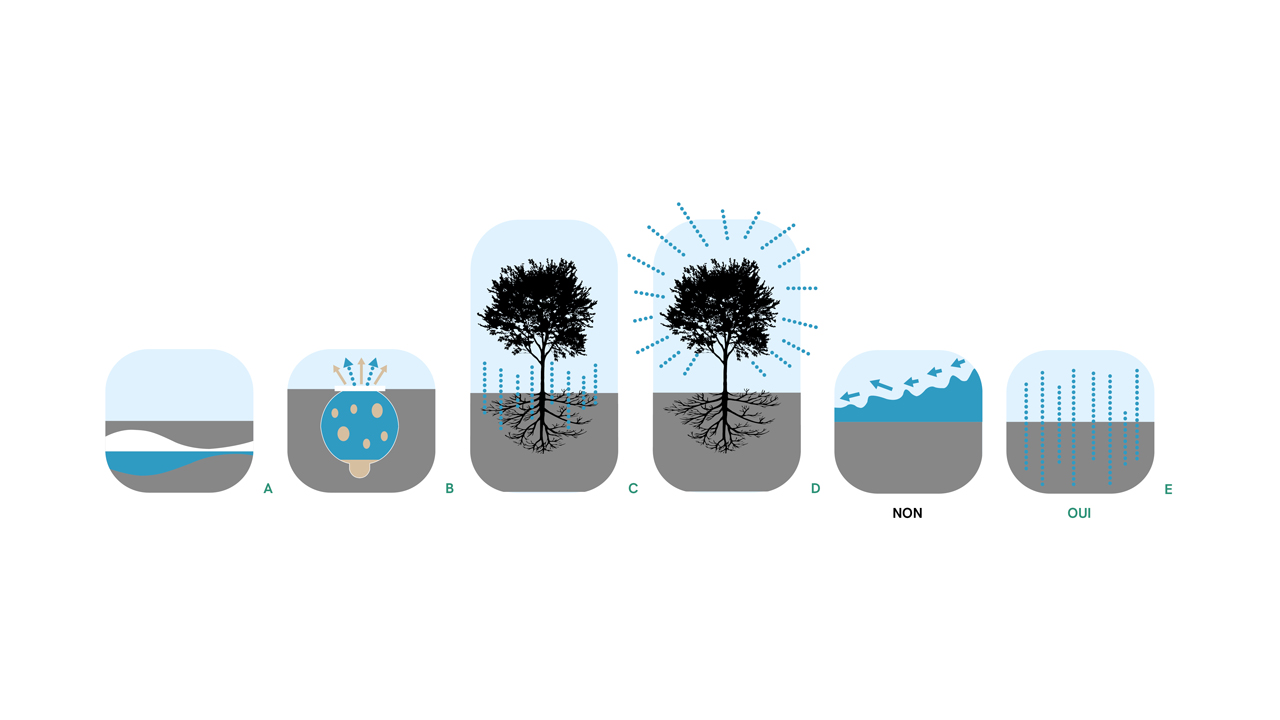

Two fundamental elements are central to our reflections in order to activate biodiversity in the city: soil and water. We want to create new practices around these two elements.

With regards to the soil: the earth is the substrate in which plants takes root. It is where they find their nutrients. In order for it to be alive, it is essential that the ground remain porous and benefit from rainwater.

With regards to water: we must preserve our water resources and stop channelling rainwater into the wastewater systems, where it serves no purpose. We must be inventive and rethink our way of conceiving of architecture and facades, in order to recycle water and use it for plant life. Let us transform wastewater into water resources!

Integrating rainwater into development projects

Integrating rainwater into development projects

Issues of sustainable development

We can no longer ignore climate change and global warming. Resilience and resource preservation are now all-important. Urban density requires us to take into account the scarcity and fragility of the elements that make up the landscape. One of these fundamental elements is water. Water is a fickle element: it can be too scarce, or on the contrary, too abundant. The IPCC report notes the increasing regularity of extreme meteorological events, such as droughts and torrential rain.

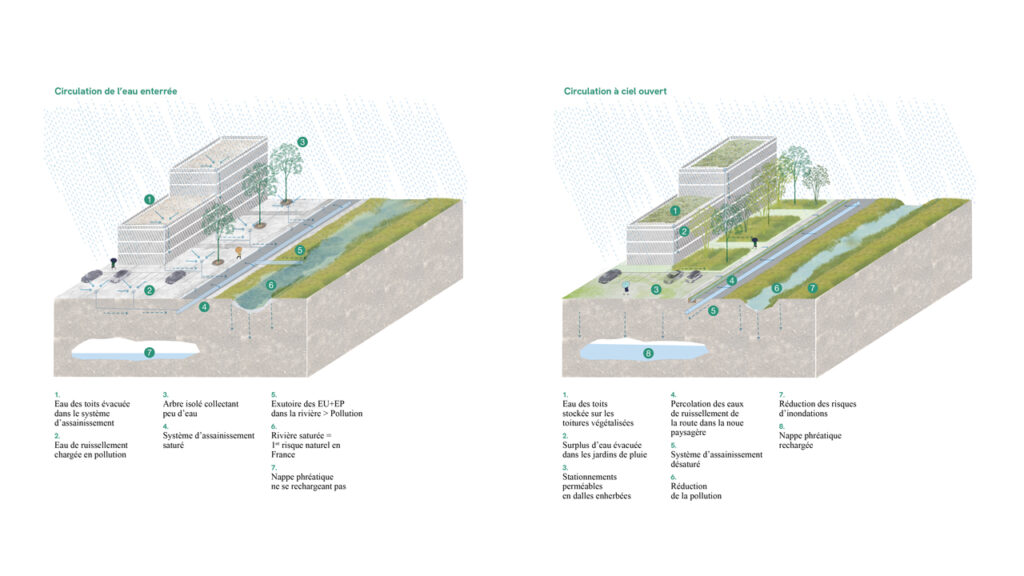

It is therefore necessary to design cities so that they can absorb these fluctuations and manage the risks of flooding. Sending rainwater to wastewater treatment plants only serves to congest the systems. In the case of heavy rain, the systems overflow and directly pollute the natural environment. In Paris, this dirty water flows directly into the Seine 25 times a year.

Open-air rainwater management presents several advantages.

De-waterproofing the ground and allowing the water to recharge the groundwater helps to reduce episodes of extreme flooding.

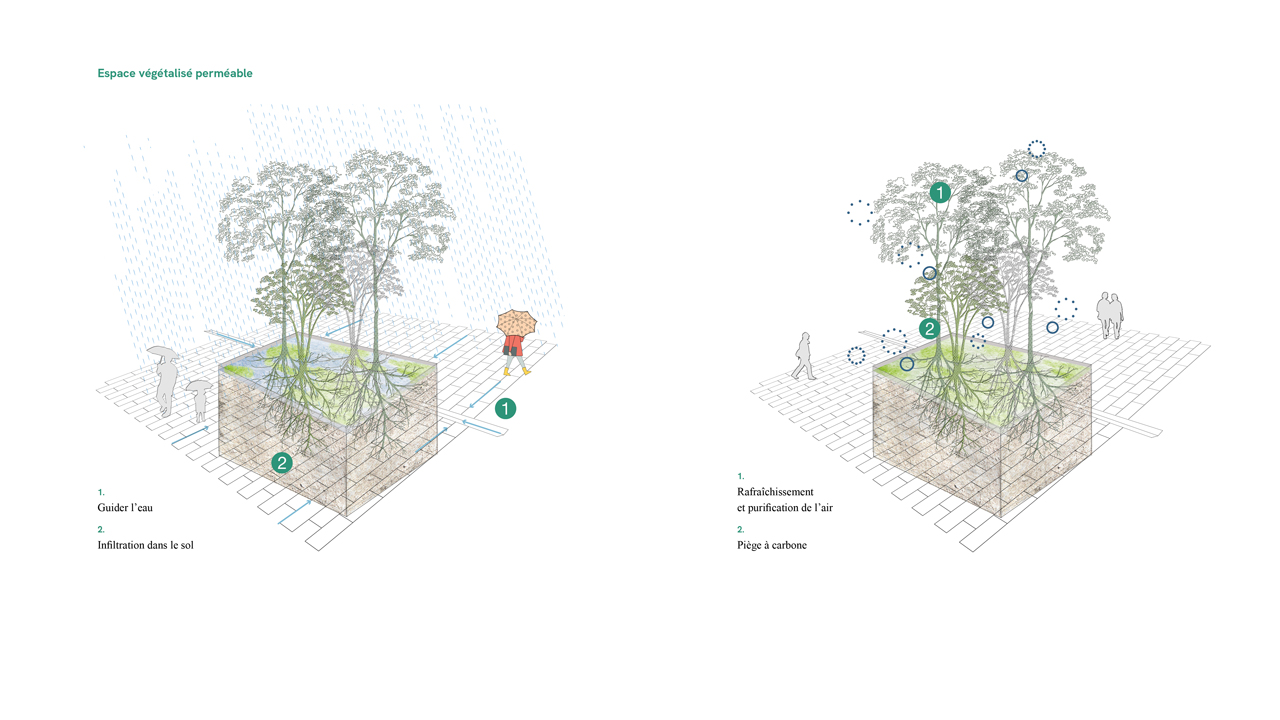

Soil and plants need water to regenerate and develop. By definition, the urban ground does not allow for living things. But as soon as it becomes porous, water can get in and plants can thrive, providing a diversified range of vegetation.

Slowing down runoff water and managing rainwater at the surface means that this water can be used for planted areas. This management contributes to the evapotranspiration of plants, and to a better urban climate.

Issues of human well-being

We are now aware of the importance of plant life for human beings’ psyches, well-being, and health. The concept of biophilia, demonstrated by several studies, shows that human beings must, by biological necessity, retain a connection with nature. The presence of vegetation in the heart of the urban environment has a positive impact on the perception of density, which is made more liveable and breathable. Highlighting the fluctuations of water across the seasons illustrates this essential component of nature: water.

Creating porous ground that absorbs rainwater contributes to residents’ well-being by generating cooler areas. In order to feel better in the city, heat spikes must be reduced. Managing water thanks to planted spaces can lower the perceived temperature by -2° to -8°.

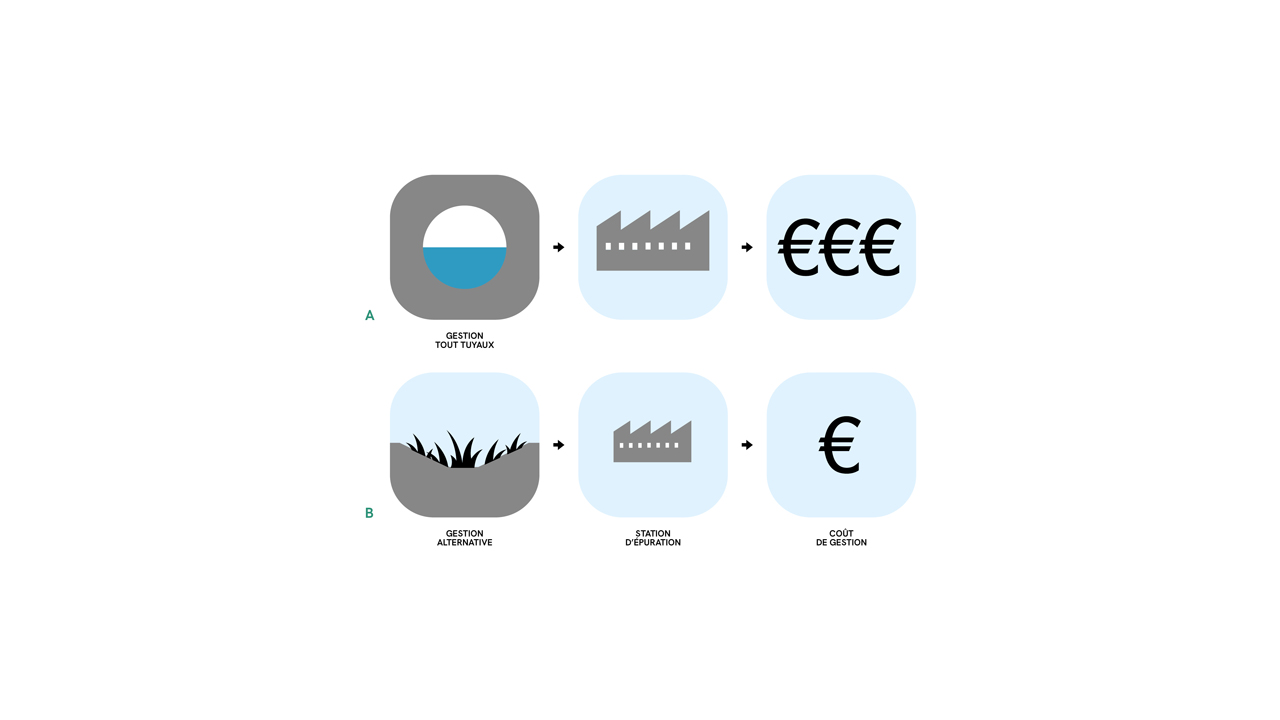

Economic issues

A third benefit of alternative rainwater management has to do with the frugality of the project.

Instead of traditional collection systems, which store water underground and direct it towards increasingly big and expensive wastewater treatment plants, it is more economical to collect water where it falls and to favour small structures that are more efficient and environmentally friendly.

On the scale of a building, we can avoid building underground storage containers, which are often expensive, in favour of planted terraces, spaces for vegetation, and rain gardens, which are not only less costly, but which also create places that are nicer to live in.

Another noteworthy element is that open-air rainwater management approaches can be subsidised by water authorities. In Ile de France, these subsidies are managed by the water authority Seine Normandie.

Which strategy to implement in order to make rainwater an asset rather than a constraint?

Integration goals in development

Using and recycling water in projects is essential, be it on the scale of a building, by avoiding channelling water into the car parks, where it becomes unrecycled refuse; by capitalising on the flow of water on the facades; by integrating it into the gardens and public spaces. The groundwater is therefore renewed, and the cities refreshed. To be efficient, this alternative rainwater management must take place on every level, from the building to the territory.

Acting for the environment necessarily involves communication and education. To help our clients with their decisions, Arte Charpentier has published Livr’eau, which demonstrates the advantages of alternative rainwater management. Livr’eau transforms our technical tools into intelligible, accessible communication tools for our clients.

Rainwater management methods for architecture, cities and territories

Buildings that integrate water management

Think organic: Calling our way of conceiving of buildings into question requires an architecture that includes different complementary and reversible uses, capable of adapting as plants do. It is not a question of a greenwashed architecture, but rather of an architecture that proceeds according to scalable rules. Water and the way in which it is integrated into a building fit perfectly into this reflection, which avoids reducing this element to a fluid calculated to flow through a pipe.

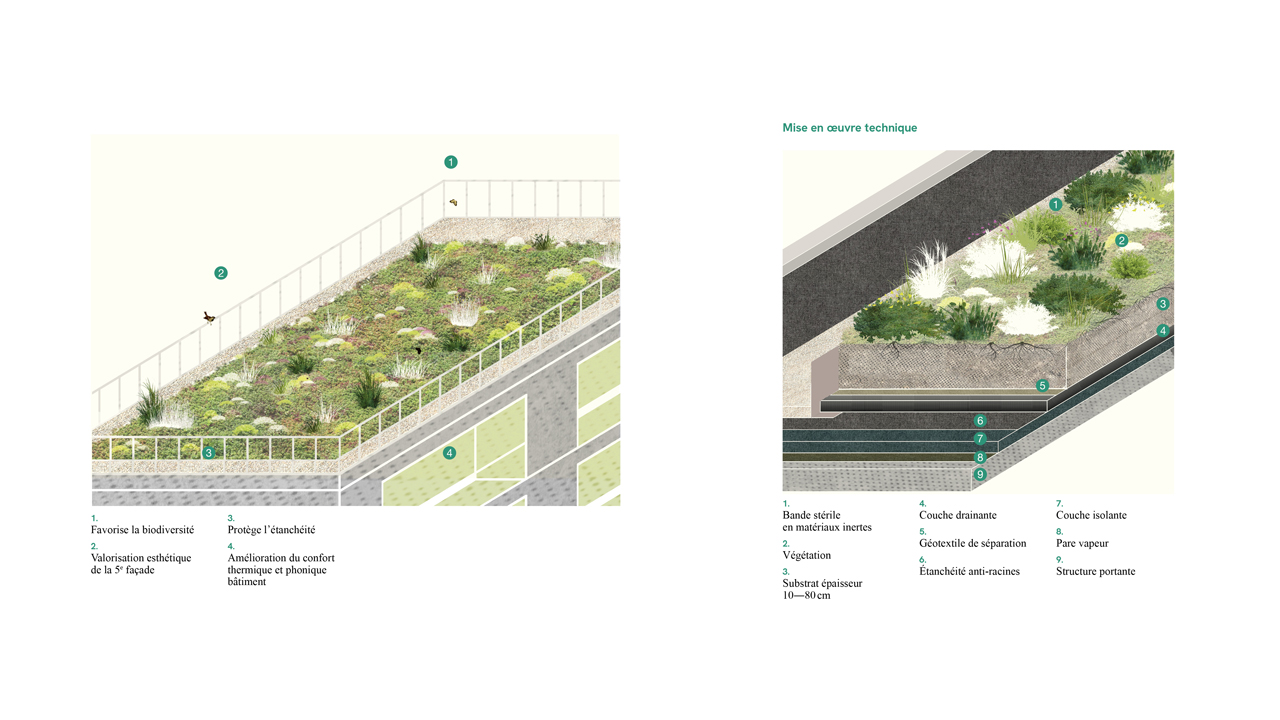

Water management systems on rooftops

In the urban environment, rooves are the first surfaces encountered by raindrops. It is therefore essential to manage rainwater starting from the rooves of buildings. Vegetation and the substrate enable water retention. Rooftops can absorb 80-85% of rainwater in summer, and 10-15% in winter.

This retention capacity delays the arrival of the water at the foot of the building. It can also be entirely absorbed by the substrate. For Paris, the Plan Paris Pluie has established a guide which specifies the correlation between substrate thickness and rainwater absorption. Hence, with a 30 cm substrate, 1-year rainfall occurrences (22mm) are 100% absorbed. With 80 cm, 5-year occurrences are absorbed.

We can therefore see the positive impact of substrate thickness on rainwater management. By playing with surfaces and thicknesses of soil, we can transform buildings into “hydraulic machines” capable of managing rainwater, whilst creating accessible planted spaces for residents and users.

The other advantage of planted rooftops and terraces concerns watertightness protection, since this absorbs differences in temperature: 5° at night, and up to 70° by day. These differences in temperature can jeopardise watertightness. In the presence of plants, the watertightness is subjected to less damages because it is protected by the vegetation. An asphalt or gravel rooftop has a 25-year lifespan, whereas a planted rooftop can help the watertightness last for over 50 years. Thermal and acoustical comfort is improved thanks to the substrate complex and the plants. Planted spaces also encourage biodiversity and accentuate the 5th façade.

Learn more about planted rooves

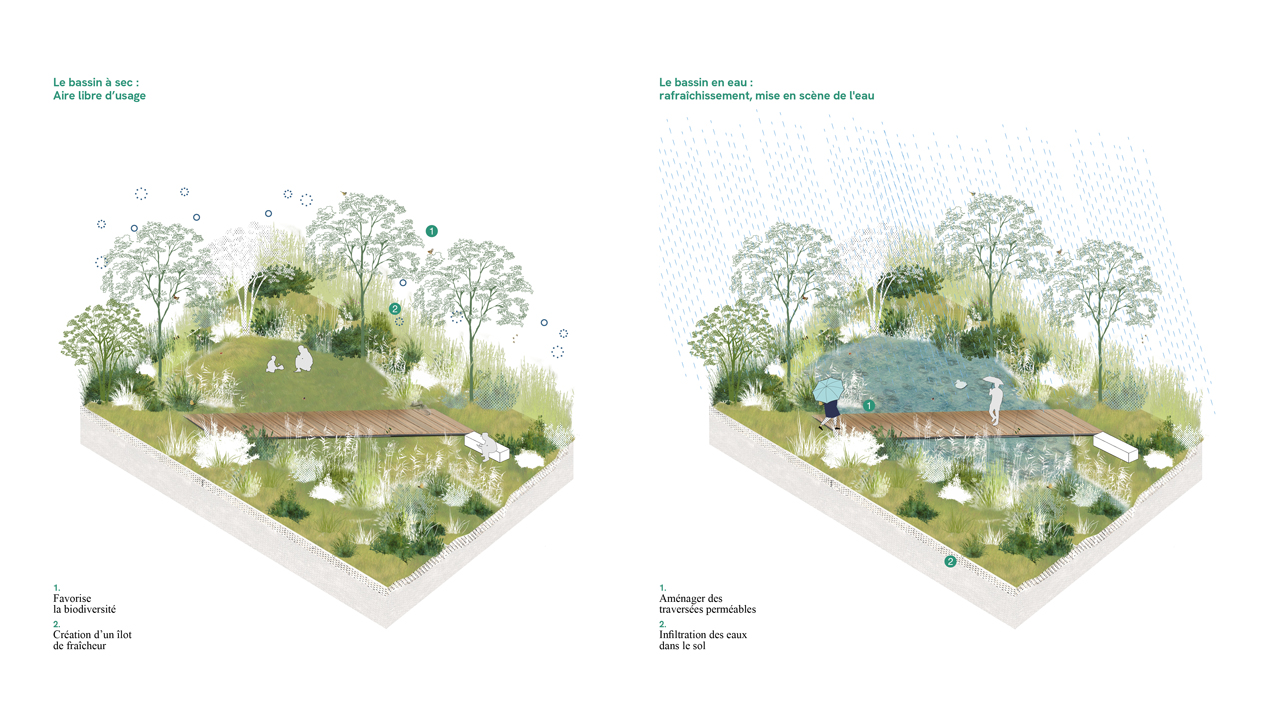

Water management systems on the facades and on the ground

Rather than channelling water into a collection system, sending it down the technical ducts to the basement, and then on to the city’s network, it is preferable to consider the recycling and capitalising of water on the facades. Rethinking gutters and downpipes, and reinventing gargoyles! Instead of seeing water as refuse to be evacuated as quickly as possible, it can become a living element integrated into the aesthetics of the building which, collected on the ground level, can contribute to refreshing the surrounding area and watering the planted spaces.

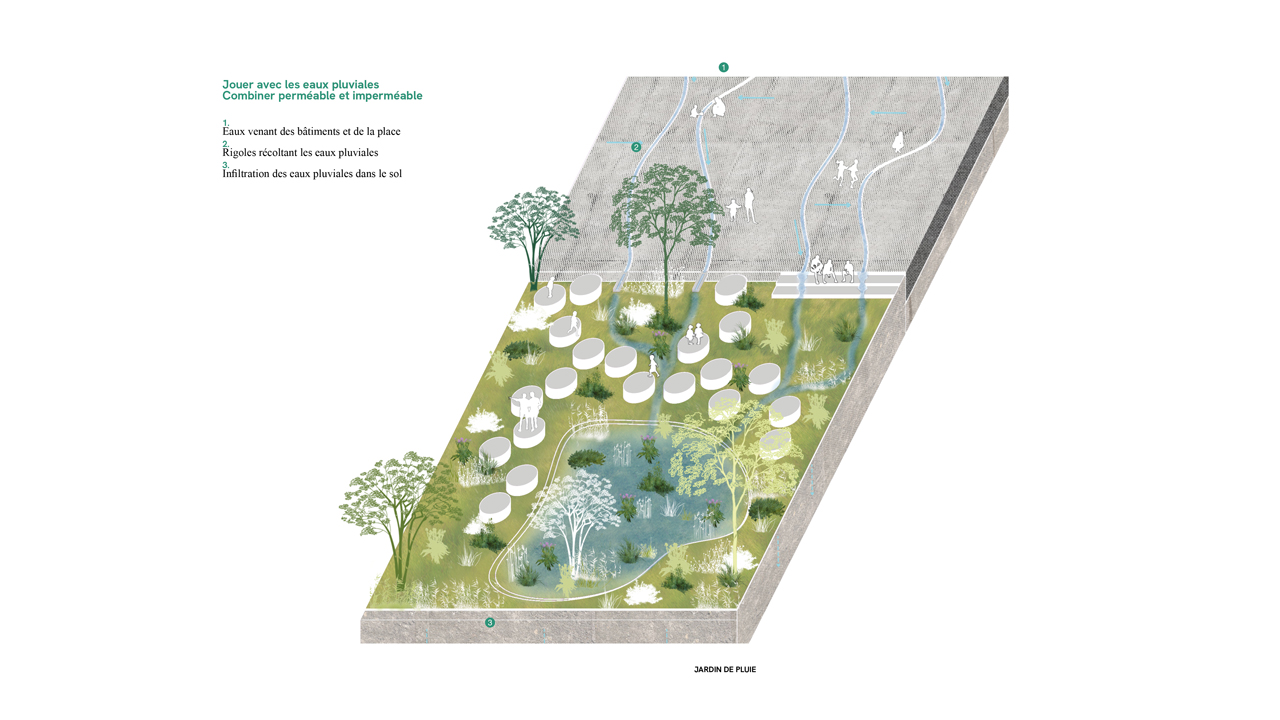

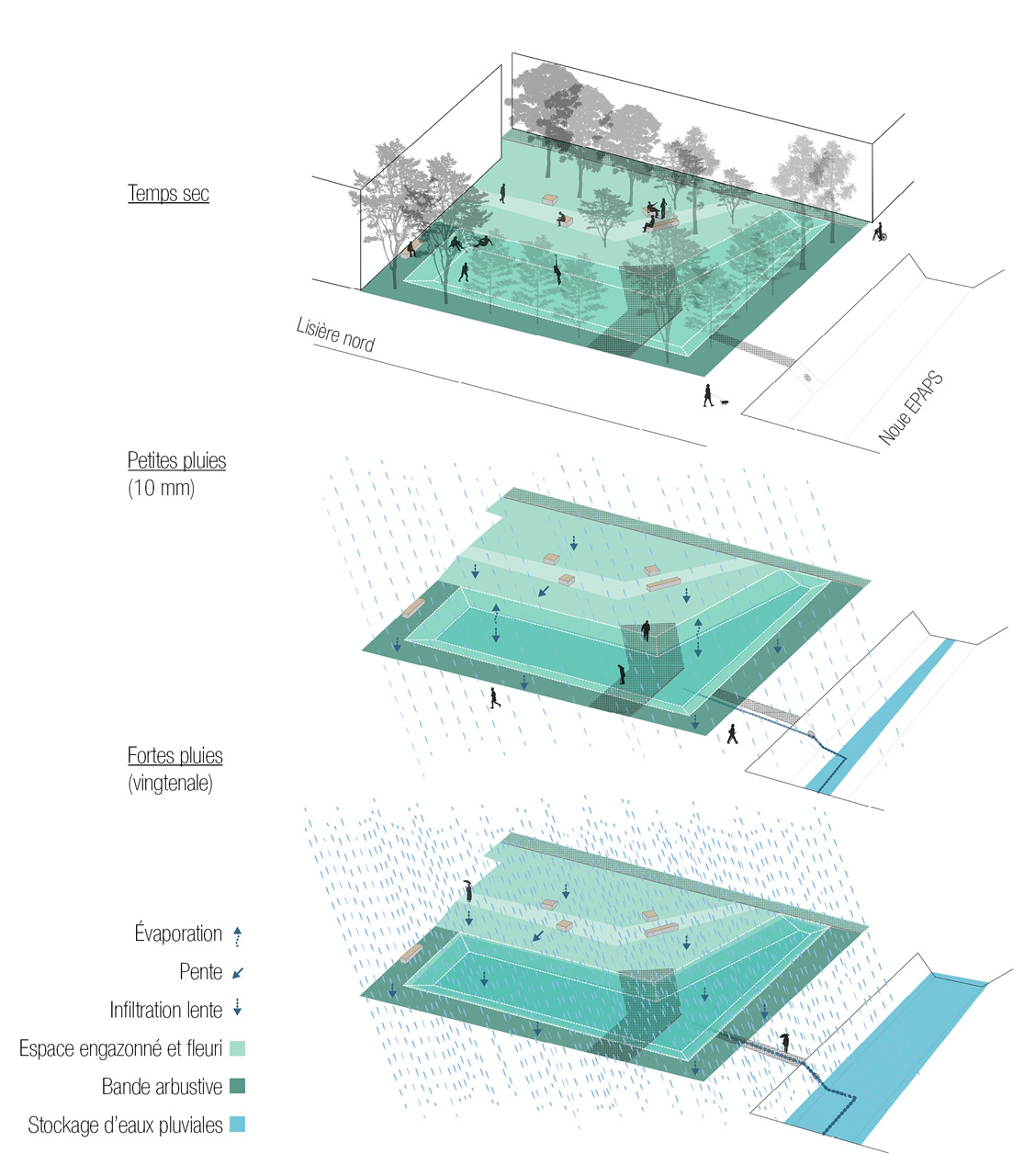

Once at ground level, water can express its potential by means of valley gutters or rain gardens, proven and efficient systems that contribute to the green belt. But above all, alternative rainwater management is a formidable tool for creation, to design spaces with multiples uses which are part of varied temporalities. Rain gardens create changing landscapes throughout the different seasons. Play areas and car parks can be designed to be partly floodable, combining porous minerals and fertile soil. Instead of providing a monospecific technical response, these spaces offer a multiple and multifunctional response. Parks, squares, car parks and play areas can also retain water, highlighting its seasonality and fluctuations, thereby reconnecting humans to nature. Rather than channelling water, seen as refuse, in underground pipes, let us consider water as the source of creation, living spaces and nature!

Focus: In’Cube

The In Cube building on the Saclay plateau, designed by Arte Charpentier for Danone for research purposes, makes use of these different systems. The landscaping project resonates with the territory, which is characterised by an historical hydraulic network, the basis for the urban sector of the new neighbourhood. At In Cube, water is recycled from the roof to the ground. The rain garden, in open ground, manages the rainwater before it is channelled into the neighbourhood valley gutters.

Permeable city, sponge city

Vegetation incorporated into the streets, pavements and public spaces has a positive impact on the perception of the city, which is made more liveable and breathable. This development of green and blue belts, and the promotion of a kind of plant invasion, should be taken even further: de-waterproofing, de-tarmacking, creating porous soil to absorb water, returning water to the ground. Creating a greener city is also the opportunity to bring residents together around a common project, allowing everybody to feel involved. It promotes conviviality between neighbours and reinforces solidarity around citizen participation.

Focus: Victor Hugo eco-neighbourhood in Bagneux

In Bagneux, the story began with the arrival of a Grand Paris station and the extension of the number 4 metro line. The idea was to densify the city whilst retaining its qualities and its diversity: the old centre, low-rises from the 1960s, streets of small, detached houses with gardens. Bagneux at the time was a green city in disguise, since vegetation was not sufficiently visible or accessible in the public spaces.

Our first action was to rework the road networks, breaking up the macro plots from the 1960s to provide more permeability and to make the planted areas, which were completely unknown to residents, more visible and accessible. Before the eco-neighbourhood, there were 3700m2 of green public spaces. Ultimately, 10 600m2 of green public spaces were created. We succeeded in densifying the city (+2000 inhabitants) whilst keeping the surface area of permeable spaces intact (with an increase from 25 to 27%).

Second action: using the green islands and connecting them in order to crisscross the neighbourhood with a green, pedestrian belt and soft mobility links. From north to south, the network of green paths connects working gardens, communal gardens, the new Ilan Halimi park, the theatre forecourt, and Robespierre Park to the south.

Third action: planting and de-waterproofing. The trees in the streets were planted in groves, and the levelling was designed so that the trees were on the path of the water. The private park, which became public, included a rain garden. A car park was requalified and de-waterproofed. Alternative rainwater management systems were installed using valley gutters, structuring the neighbourhood as a whole: the green belt was enriched by a blue belt.

Resilient territories: developing cities based on the key elements of the landscape and geography

Recent events have shown that we must now live with climate risks. We must implement strategies to prevent floods in order to minimise disasters, and integrate the risk into urban projects. On the scale of a territory, it is even more essential to take the geographical data on topography and hydrography into account, in order to restore ecological functioning and create permeable cities capable of absorbing water surpluses.

Focus: Franco-Chinese Eco-city of Caïdian

Located in Wuhan, China, this developing city is part of a water territory, with an omnipresent hydrographic network, but where aquatic environments are undervalued. The future city is surrounded by lakes to the north and south, within which some aquaculture remains. We developed the masterplan by designing green corridors linked to the existing natural hydrographic network, enabling intelligent rainwater management. This region of China is known for its heavy rains and the authorities asked us to take into account a fifty-yearly level rather than a ten-yearly one. This is a significant amount. To avoid the multiplication of underground structures, we imagined open-air systems which enabled the creation of bigger public spaces. The block plan was based on the landscape and on the alternative rainwater management systems. The work on water had an undeniable effect on our way of designing this new part of the city.

-

Nathalie Leroy Landscape Designer, Associate

Landscape Director

EDUCATION

Landscape Architect DPLG – École Nationale Supérieure du Paysage de Versailles

Textile Design Diploma – École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris